- Home

- Irvine Welsh

The Bedroom Secrets of the Master Chefs Page 2

The Bedroom Secrets of the Master Chefs Read online

Page 2

Danny Skinner felt his bottom lip curl outwards, the way it always seemed to when he was undermined and forlorn. He’d done his job. He’d told the truth. Skinner was no naive fool, he knew the realpolitik of the situation: some were always more equal than others. But it stuck in his craw that if a Bangladeshi immigrant with a last-orders curry house had a kitchen as minging as De Fretais’s then he’d probably never a boil an egg in the city again. — Right, he said miserably.

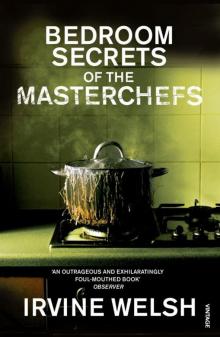

But maybe he had spiced it up a bit. He didn’t like De Fretais, even if he found the man strangely compelling. His copy of The Bedroom Secrets of the Master Chefs was a guilty lunchtime purchase, and it lay concealed in his briefcase. He recalled the opening paragraphs of the foreword, which he’d read with such distaste:

The wisest in our midst have long known that the simplest of questions are often the most loaded. With every student of the culinary arts who comes into my orbit, I endeavour to begin our relationship by asking the question: who is the Master Chef? The responses are never less than instructive and intriguing to me, for in order to assist in my quest for culinary excellence, it’s this very question I perennially seem to address.

For sure, our Master Chef must be an artisan: a craftsman who takes a stubborn pride in the painstaking and often mundane details of his métier. Certainly the Master Chef is also a scientist. But he is more than just a chemist: he is an alchemist, a sorcerer, an artist, as his concoctions are not designed to remedy maladies of body or mind, but attend to the far more wondrous task of uplifting the soul.

Our vehicle for the achievement of this objective is food, pure and simple, but this journey must take us along the road of our own human senses. So, I contend to my oft-bemused students, and now to you, dear reader, that if the Master Chef is anything, then he is, and must always be, a complete and utter sensualist.

He’s just a fucking cook, and so many of those cunts are too big for their boots.

And this fucking guide to sexy food! That fat cunt! The whole thing’s ridiculous, it’s been a good few years since that phantom’s seen his fucking prick without the help of a mirror! And those fucking anodyne, sexless yuppies would respond to that, they would actually buy it in their thousands and make a fat, rich, spoiled cunt fatter, richer and more spoiled still. And here I am with a fucking copy in my bag!

Watching Skinner’s complexion redden, Foy felt a slight unease and removed his arm. — Danny, we can’t be rocking boats at this time of the year, so no pub stories from the horse’s mouth about how bad our friend De Fretais’s kitchen is, okay?

— Goes without saying, Skinner replied, trying to conceal a mounting excitement that in the boozer tonight he’d blab to everyone who would listen.

— That’s the spirit, Danny. You’re a good inspector and we certainly need them. We’re down to five in the inspectorate, Foy shook his head in disgust, and then quickly brightened up. — Mind you, our new laddie starts tomorrow, the one from Fife.

— Oh aye? Skinner raised his brows enquiringly in an unwitting impersonation of his boss.

— Aye . . . Brian Kibby. Seems a nice young chap.

— Fine . . . Skinner said distractedly, his thoughts drifting to the weekend. He’d have a few bevvies tonight; these four pints at dinner time had given him a fair old thirst. Then, barring the football on Saturday, he’d spend the rest of the weekend with Kay.

Everybody had his or her own idea of where Edinburgh ended and the port of Leith commenced. Officially, they said it was the old Boundary Bar at Pilrig, or where the EH6 postcode started. For Skinner though, coming down the Walk, he never truly felt back in Leith until he could feel the hill levelling out under his feet, which was a great sensation, like his body was a spacecraft, landing home after a long voyage to inhospitable lands. He generally marked this from the Balfour Bar onwards.

On his way back home, Skinner decided to stop off at his mother’s, who lived across the road from her hairdressing business, in a small cobblestoned alley off Junction Street. That was where he’d grown up, before moving out the previous summer. He’d always wanted his own place, but now that he had it, he missed home more than he could ever have imagined.

The Old Girl’s finished her shift and she fair stinks of thon perming lotion. I’d forgotten how much the whole gaff reeks of it, how it permeates. She’s still got that Indian-ink home-made BEV tattoo on her forearm, making zero attempt tae conceal it, even when she’s working directly with her customers in her service industry business. Admittedly, wir no talking fussy client base here: a million miles removed fae the sorts who would patronise, say, fat boy De Fretais’s restaurant.

I grew up hanging around that shop, where every old boiler of a regular was a surrogate auntie or gran. I was smeared, like a luxury unguent, intae aw thon meaty bosoms. A wee boy without a daddy: to be pitied, spoiled, loved even. Good old sunny Leith: no place loves its bastards like a port.

The electric-bar fire with its fake coal display throws out some heat, but her big, blue fluffy Persian cat lies sprawled out on the rug in front of it, absorbing all the warmth like the selfish fucker it is. The art deco mantelpiece bordering it is usually the centrepiece of the room, but it now takes second place to an overwhelming, outsized Christmas tree in the corner. On the wall, above the fireplace, hangs a mounted copy of the Clash album London Calling. Scrawled on it by Magic Marker ink is:

To Bev, Edinburgh’s No.1 punk,

Luv Joe S xxx

20/1/80

The Old Girl’s great conceit is that she’s a student of human nature, having convinced herself that, in her line of work, she can read a person like a copy of Hello!. When they come in and tell her they’re thinking of having this or that done to their dry, cracking or lank, greasy locks, she looks them in the eye and goes: ‘Ye sure that’s what ye want?’ They’ll stare nervously back at her and throw out some hopeful possibilities till she nods approvingly and says, ‘That’s the one.’ Then she’ll cheerfully expedite this, cooing ‘It’s awfay nice’, or ‘It really suits ye, hen’. And they keep coming back. As the Old Girl often boasts, ‘Ah ken thum better thin they ken thirsels.’

Unwelcome, however, is the application of this attitude in her dealings with her solo bastard offspring. She sits in her chair as I slump on the couch, hitting the handset and switching on Scotland Today. — That compo money, she begins, narrowing her eyes under those big specs, — suppose that’s aw in the hands ay the publicans by now, eh?

The Old Girl’s expanding out the way. She’s always been a short-arse, but now her face is getting fleshier. As she’s always favoured black, she gets no slim-effect pay-off on her middle-age spread. — Grossly unfair, I say as the sports round-up comes on and another Riordan goal bursts the net, — there’s a number of bookies who’ve had their cut.

But she’s taking the pish here. She knows how much it cost to put a deposit on that flat. It was fifteen grand I got for that accident, no a hundred and fifteen!

— So it’s aw been squandered? she says, running her hand through her crimson hair.

I’m not getting into this with her. — To paraphrase a great footballer: ‘I spent most of it on drink, women and the horses. The rest I squandered.’

— Aye, right, the Old Girl snorts, rising and putting her hands on her hips, unwittingly mimicking the pose struck by Jean-Jacques Burnel in the Stranglers poster on the wall behind her. — Suppose yir steyin for yir tea?

This is seldom the gastronomic treat she imagines it to be. —What ye got?

— Sausages.

Hud me back. — Beef or pork?

The Old Girl whips her glasses from her face, leaving wine-coloured indentations on each side of her nose. She struggles to refocus, looking like she’s just woken up as she brushes the lenses on her blouse. — You wantin yir tea or no?

— Aye . . . awright.

— Dinnae dae ays any favours, Danny, she muses, breathing on her lenses and wiping them again. She puts them back on and heads across to the galley ki

tchen, where she opens up the fridge.

I get up and move across to the kitchen area, draping myself over the breakfast bar. — Maybe I ought to have invested my money in commodities. Something popular and durable, I stretch across, poking the tattoo on her arm, — like Indian ink.

She pulls away, glowering at me through those specs. — Dinnae start, son. And dinnae think you can be paupin oaffay me aw the time. You’ve a good job: ye can pey yir ain credit card bills.

Every time I come here I get reminded about fucking bills. My Old Girl still likes to think of herself as a punk, but she’s a small businesswoman to her marrow.

3

The Outdoor Life

THE BRACKEN WAS thinning out as the gradient of the hill rose steeply. Brian Kibby, his too large Aran sweater and waterproof anorak flapping in the wind, wiped some sweat from his brow under a baseball cap, which was fastened so tightly that it hurt. He took a deep breath, feeling the cool, mountain air clearing out his lungs. As the life fused through his wiry frame, he stopped at his vantage point, turning to look back across at the great range of Munros, and the sweep of the valley curling beneath him.

As he enjoyed his sense of oneness with the world, a righteous notion seized him: this was the best thing he’d ever done, going along to the hillwalking club with Ian Buchan, his only friend from his schooldays, who remained his special companion. They had met through a shared mutual love – video games – and had attempted to convert each other to their own great passions. Ian was one of the few people who had been allowed to set foot in Brian Kibby’s attic, with its much coveted model railway, though Kibby knew he had little real interest. And though he himself only tolerated Ian’s Star Trek obsession, his devotion to hillwalking was for real.

Brian loved his weekends with that wholesome, hearty bunch, rejoicing under their collective title, the Hyp Hykers. It had greatly pleased his ailing father that he was getting out more and had a pal, even if Keith Kibby was doubtful about the somewhat exclusive nature of his son’s friendship with Ian Buchan and even more so about this Star Trek obsession. Even up in the desolate hills, his father’s condition seldom strayed far from Brian Kibby’s thoughts. His dad was very ill now, and had seemed so weak and frail when he’d visited him in the hospital the previous night.

Brian Kibby licked at the salt that was tainting his lips, and after the effort of the trek up the path by the side of the hill, raised the bottle of Evian to his mouth. Looking down the valley in some trepidation towards the biggest mushroom cloud of midges he had ever seen, he felt the mineral water massage the back of his dry throat.

Replete with the sense of himself, he gaped in wonder down across the deep gorge over to the stark, sweeping hills above him, the scene scored by Coldplay’s Parachutes album, which played on his iPod. Switching off the machine and pulling out his earphones, he let the natural silence, broken only by the faint squawking of some overhead birds, resonate for a bit. Then a sudden sound of thicket crushing underfoot signalled a presence by his side. Assuming it was Ian, he said without turning, — Look at that, it makes ye feel great tae be alive!

— It’s beautiful, a female voice agreed, as Kibby experienced panic and elation rising in his breast and vying for dominance. As he turned round he felt his cheeks burn and his eyes moisten. It was Lucy Moore, with her intense blue eyes and those blonde-brown curls, which were whipping recklessly in the wind, and she was talking to him. — Eh . . . aye . . . he managed to cough out as his eyes fell on her scarlet slash of a mouth.

Lucy seemed not to notice Kibby’s awkwardness. Her composed but piercing eyes scanned the mountains across the valley, the tops of which were dusted white with snow, before settling on the highest point. — I’d love to have a go at climbing it, she said, glancing conspiratorially at him.

— Naw . . . eh . . . hillwalking suits me just fine, Kibby responded lamely, immediately regretting it as he sensed her vague interest in him steadily draining away. Worse, it was replaced by the aura of mild contempt he habitually appeared to induce in many members of the opposite sex. — Mind you, it is tempting tae give it a go . . . he added, striving to recover his standing.

— I’d love to, Lucy reiterated, advancing again but more tentatively. Kibby didn’t know what to say and lisped out, — Aye, it would be great, right enough.

There followed a silence of such excruciating embarrassment that Brian Kibby, who had reluctantly managed to get through his teens and the first year of his twenties without so much as kissing a girl, would unquestionably have traded a lifetime of virginity simply to be free from its torment. Blood bubbled in his face, tears welled in his uncontrollably blinking eyes, snot ran in a steady stream from his nose and his throat dried up to the extent that he knew if he attempted to speak his voice would crackle like the dry twigs under his feet.

The impasse was only broken when Lucy asked wearily, — What time is it?

Kibby was so eager to be free of his torture that in his haste to respond he caught the elasticated cagoule cuff on his watch strap, ripping the garment slightly. — Nea-nearly two, he stammered.

— I suppose we’d better get back to the bothy for our meal, Lucy mused, regarding Kibby in a quizzical manner.

— Aye, Kibby trilled, perhaps a little too highly, — or these gannets’ll have the lot!

And something collapsed inside of him when he saw the slightly sad smile he elicited from her. For he knew that same look from his sister, her friends, and the girls from the office: he saw it in every young woman of his acquaintance. He took off the red baseball cap and stuck it in his pocket, feeling his temples breathe.

The stone walls of the quarry were steep and grave, as stark as a row of tombstones in a cemetery. From the banks of the man-made lake opposite, Danny Skinner looked at the wizened trees twisting upwards, trying to find light in the foreboding shadow the big stones cast. It had been raining all day. Now it had stopped, leaving a dusky sky with the promise of a damp, shivering night ahead.

A cold was settling into his chest already, aggravated by the cocaine-fuelled stream of mucus that trickled steadily down the back of his throat. He looked around at the three ill-clad men beside him. In a predatory manner, they were regarding two other men who were fishing in the quarry and who were more appropriately dressed for the seasonal inclemencies. Big Rab McKenzie, six foot four and overweight, was his best mate from way back at school, and still his best drinking buddy. Gareth he didn’t know that well, they’d only been friends for a few weeks, but Skinner had liked him by his reputation before they had even met.

It was Dempsey who made him uneasy. Despite his relative youth, the diverse circles that he flitted around in meant that Skinner had met quite a few name hard men, even the odd psychopath. He noticed, though, that once they got to a certain stage of development, they generally only swam with other sharks. But there was something ubiquitous and consuming about Dempsey. Very useful in certain street confrontation situations certainly, but definitely miscast here. Or, Skinner reflected, perhaps it was he who was miscast.

They were all football mates and the waterlogged pitches had wiped out the fixture list across the country. But that was what they did; they mobbed up on a Saturday and had a bit of harmless sport; sometimes a punch-up, usually just posturing. But, Skinner asked himself again, what was he doing in a quarry in West Lothian on a pissing December Saturday evening?

The answer had been cocaine. Earlier, in a pub in the city, Dempsey had chopped out line after line as the company had whittled down to the four of them. Then he’d suggested a little adventure in the country. It had seemed fine at the time, a scheme formulated in a warm city pub full of drug bravado. Now, out here, it had gone from exciting to dubious to plain boring. Skinner wanted so badly to be at home with Kay.

He had told her that, in the absence of the football, he was going fishing with some of the boys. It was unlikely but was actually almost true. But he knew that he should be with her now, so he grew anxious. He hopefully reca

lled that she’d mentioned something about dance rehearsals. They could go on. But he was still fretful, though perhaps not as much as the two anglers seemed to be.

— Well stocked wi pike, the quarry, Skinner, trying to lighten things, explained to the two fishing lads. — Used to be aw perch. So they introduced a couple of pike, like: ‘pike–lake, lake–pike’, he motored on, scarcely waiting for a reaction but noting Dempsey’s twisted smile, — and the cunts tore through the perch stocks. Decimation job. He turned to his friends. — Got so fuckin low oan perch that the locals were flinging in the wooden spars fae their budgerigar cages, jist tae make the numbers up! And Skinner’s coffin-plate dazzle of a smile was forming involuntarily as he smelt the fear rising in the angling boys. He sensed they caught the nakedness of his base response and it briefly belittled him.

And the insipid setting sun was covered by another wave of renegade black clouds, sending a filthy shadow racing across the lake causing one fishing lad, one with ginger hair, to visibly shiver. McKenzie, feeling moved to react to this, kicked over the box of fishing tackle and bait. Live maggots squirmed in the mud. — Clumsy ay me, eh?

Skinner gritted his teeth and exchanged a knowing look with Gareth that said: trust McKenzie to let the side down by embarrassing us with such a corny line, delivered so shockingly as well.

— Fae up the coonty, then, boys? Dempsey asked. — No attached tae any mob, ur yis? he enquired of the bemused lads before pointing and raising his voice to one boy: — Ginger cunt! Ah asked ye, what fuckin team dae ye support?

— I dinnae follow football . . . the boy started.

Dempsey seemed to consider this statement for a second or two, nodding his head in appreciation, like a toff savouring a fine wine on his palate.

If You Liked School, You'll Love Work

If You Liked School, You'll Love Work Ecstasy: Three Tales of Chemical Romance

Ecstasy: Three Tales of Chemical Romance The Sex Lives of Siamese Twins

The Sex Lives of Siamese Twins Trainspotting

Trainspotting Filth

Filth Glue

Glue Marabou Stork Nightmares

Marabou Stork Nightmares The Bedroom Secrets of the Master Chefs

The Bedroom Secrets of the Master Chefs Dead Men's Trousers

Dead Men's Trousers The Blade Artist

The Blade Artist Crime

Crime The Acid House

The Acid House Skagboys

Skagboys Ecstasy

Ecstasy